- Winterkeep, by Kristin Cashore. I had some problems with this one, though I did read it all the way through, not just once but twice. Kristin Cashore is one of “my” writers and so her works get a level of trust from me that many other authors’ don’t. For this reason I found reading Winterkeep an interesting exercise in figuring out what my problems with it were. I think it comes down to three main issues (no real spoilers in what follows). First is a world-building issue. Cashore’s previous novels in this universe (Graceling, Fire, and Bitterblue) suffered from a common and extremely problematic issue in fantasy: presumed (and in some cases explicit) whiteness (some discussions of this issue in fantasy generally here and here). Perhaps in part to remedy this, in Winterkeep Cashore presents a nation of people with brown skin, and clarifies that the Lienid are also brown-skinned (albeit lighter-skinned than the people of Winterkeep). All this is well and good, except that by this choice, Cashore has created a world in which human phenotype is completely unmoored from biological reality (the people of Winterkeep live in the far north). This worldbuidling thus gives credence to some mistaken ideas about the biology of skin color and race; such mistaken ideas inform quite a bit of present-day scientific racism (this project provides some background for what I’m trying to get at here), which is clearly not what Cashore intends – but nonetheless, it bothered me. I couldn’t not see those threads as I read. My second issue is also science-related. While environment is at the heart of the conflict in Winterkeep, and Cashore emphasizes this by having two point-of-view and one additional important set of non-human animal characters, all the animals seem completely human-focused. These three types of animals are the only wild animals we’re introduced to (and one, the telepathic foxes, would really have to be considered a semi-domesticate); otherwise the world is populated by domestic animals (that is, dependent on humans) such as cows, pigs, and cats. This wouldn’t be too much of a problem except that the responsibility of the denizens of Winterkeep to take care of the earth and the impacts of their decisions on ecosystem dynamics are a significant part of the plot. Similarly, while concepts such as cascading environmental effects and ecosystem mechanics are touched upon, the superficial way in they are treated supports the idea that people are the superior beings, the most important part of this world…which is directly in conflict with the stated environmental themes of Winterkeep. Finally, one of the aspects of this book that I really liked was the theme of coming of age out of a background of family trauma. However, the many viewpoints (there are five) made it hard for me to fully connect with the character of Lovisa. And this made the way in which Winterkeep treats family trauma, for me, fundamentally unsatisfying. Together these three issues made the entire book problematic for me; they may not be so much of an issue for other readers. But thinking about why things were problematic for me in this one was also a really fruitful and interesting exercise – one that’s given me some insights into writing craft.

- Interior Chinatown, by Charles Yu. I loved this book.

- The Banished Immortal: A Life of Li Bai, by Ha Jin.

- Making Magic: Weaving Together the Everyday and the Extraordinary, by Briana Saussy

Writing resources

I have been thinking about a post describing how I began writing again after a hiatus of fifteen years. Writing journey stories always fascinate me, no matter how prosaic, and I feel like writing my own might be useful for me as well as potentially interesting to others. I sat down and began it — but it soon became evident that the story of my writing journey is not yet ready to be told. The right words aren’t available to me yet. Someday they will be, but at the moment the topic is, as Natalie Goldberg would say, “composting.”

Instead, I will share something related: a list of writing resources. The list below contains things – mostly books, but also a set of videos – that I have found useful in writing. Some of them were useful in the past, even transformative, but more recently have been less so (although maybe they will be again sometime). Some I revisit again and again, finding something new each time; some were more useful to me years ago than they are now, but they’ve stuck with me and are part of my canon. They are not all directly about writing, and they contradict each other. Some of them, even, are internally inconsistent. But they are all resources that have helped me on my writing journey, as my driving question has changed from, why do I write? to, how do I write?

In most cases, the links for books go to my local indie, Bookworks, but the books are available elsewhere too (most of them – Second Sight is hard to find these days!).

- Writing Down the Bones and Thunder and Lightning, by Natalie Goldberg. Writing Down the Bones is a very well-known book, more than thirty years old now, which (despite my abiding love for writing books) I only discovered this past summer. Goldberg’s approach is all about writing practice; what she means by that is the topic of Writing Down the Bones, while Thunder and Lightning covers what to do with a writing practice, after you’ve established one. Goldberg has been instrumental in getting me writing again…or maybe it would be more accurate to say, in getting me to love writing again. In addition to her books, Goldberg teaches workshops, some online, one of which I attended this past June/July. If you have the opportunity to study with her, whether through her workshops or her books, I highly recommend it!

- Zen in the Art of Writing, by Ray Bradbury. This short collection of essays is an old favorite of mine. Although they are more personal essays than writing guide, they are filled with practical advice on how to write. And that advice is not dissimilar to Goldberg’s, although Bradbury and Goldberg are completely different writers. As someone who writes speculative fiction, I find the pairing of this volume with the two from Goldberg, above, extremely helpful.

- Steering the Craft, by Ursula Le Guin. This one is a guide; it is a finer-grained look at writing than the Goldberg and Bradbury books, being full of exercises that focus on language. A class on how to use language from Ursula Le Guin – who couldn’t use such a thing? (Probably someone, but I can sure use it!)

- Second Sight and The Magic Words, by Cheryl Klein. Klein, currently the editorial director at Lee & Low Books, self-published Second Sight, a collection of her talks and essays (out of print now, although Amazon lists some used copies) and then later went on to publish The Magic Words, a more formal writing guide, with Norton. Klein describes herself as a “narrative nerd” and these two books are my go-to guides for thinking about how to shape a narrative. Klein’s editorial specialty is children’s and young adult literature, but much of what she has to say applies to any writing – even non-fiction.

- On Writing, by Stephen King. I was not really a Stephen King reader, though his books were wildly popular among my peers (I love this interview and most particularly Victor Lavalle’s description of his early Stephen King-influenced writing; I was busy writing similar knockoffs of Mary Stewart, which didn’t resonate so well with my friends). On Writing is part memoir, part guide, and just amazingly well-written.

- Something to Declare, by Julia Alvarez. This book of autobiographical essays by Alvarez – one of “my” writers, writers who have written books that have become part of me – is more about her life (including her life as a writer) than about the mechanics of writing. It’s not a textbook, in other words. But writing and reading are the backbone of these essays, even the ones that are about Alvarez’s life as a child rather than writing per se, and I have learned much about writing from all of them.

- Brandon Sanderson’s lectures from his BYU class. Links for these can be found here https://www.brandonsanderson.com/writing-advice/; there are other versions out there too. I listened to the audio from the 2014 version fully (these seem to have been taken down at this point), and have watched only some sessions from more recent years – but as far as I can tell, the more recent classes cover the same ground.

Into the new: reflecting on reading and writing in 2019

December is, for me, the season of reflection. For the past week or two, as things have wound down at work, in the garden, everywhere, I’ve been thinking about reading and writing – what I’ve been doing over the past year, and what I’d like to change.

I didn’t get as much writing done in 2019 as I had hoped I would; there’s nothing new in that (does anyone ever get as much writing done as they had hoped?). I *did* have breakthroughs with a couple of different projects that were stalled at this point last year, and I know how I want to proceed with them now. The trouble is that I have too many concurrent projects going, and it’s not yet clear to me which of these I will pursue first and which will wait. This decision is at the forefront of my reflections right now. I will decide this, sometime over the next few weeks, and we will see.

On the positive progress side of things, I was able to return to reading in 2019. I read lots, and I wrote about reading, too (here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here). I’m happy about this – both the reading and the writing about it. My reflective reading brain is slowly creaking to life again, it seems. I am so glad to have it back.

And yet, despite this, I’ve been frustrated by my reading lately. This has happened before (and it’s a not-uncommon experience), but, this year (and maybe in previous years also, I don’t know) and for me, I think my frustration isn’t a purely internal phenomenon. I think it has to do with what’s being published, at least in part (this and this and this contain some previous related reflections).

When I’ve felt this in previous reading slumps, I’ve pushed back against my instincts, telling myself it’s all internal. And maybe I was right; I did manage to get out of those previous reading slumps. But this time, I’m going to try something new to address this. Following up on some recent thoughts on self-publishing/small presses, I’m going to try to devote a majority percentage of my 2020 reading to works published by small and independent publishers, rather than by the big 5.

I’m still working out how I will actualize this, but I’ll write about it here as I figure it out.

Listening

I have been listening to Performance Today this morning, featuring Andre Watts and Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Piano Concerto. When asked about his relationship with his teacher Leon Fleisher, Watts said that the most important thing Fleisher taught him was to listen – to listen to everything.

It reminded me when I took a class in drawing, many years ago. The class’ first rule was to really look, to see.

Writing, like music and drawing, sharpens my senses. Look, listen, touch: such small things, all a part of everyday life, and yet magic when given full attention.

Q&A with Scott Hawkins, author of The Library at Mount Char

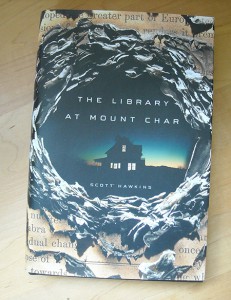

Last week I posted about reading (and enjoying) The Library at Mount Char. Author Scott Hawkins was kind enough to answer a few questions for me, providing (among other things) some thoughts on fantasy libraries, a recipe I can’t wait to try, and advice for librarians engaged in power struggles at work. Thanks for the great answers, Scott!

******

I’ve seen The Library at Mount Char described as urban fantasy, as horror, and as speculative fiction. How do you think of it, and why?

I’ve seen The Library at Mount Char described as urban fantasy, as horror, and as speculative fiction. How do you think of it, and why?

I think of it as fantasy, but ‘speculative fiction’ works too. I was a little surprised to see that some people think of it as ‘horror.’ I mean, that’s fine, think of it however you want, I just wasn’t expecting it. I knew that there were horror elements, of course, but I miscalculated the degree to which some people found them disturbing. I thought I had the horror dial turned up to maybe 5 or 6 out of 10, but based on the reactions it seems like it was more a 7 or 8.

Continue reading “Q&A with Scott Hawkins, author of The Library at Mount Char”